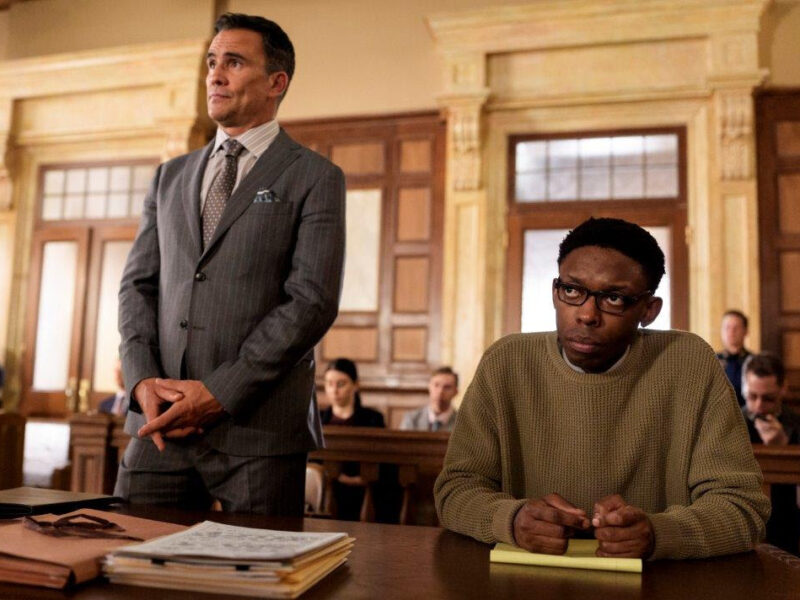

The Netflix miniseries Adolescence is not just a gripping psychological drama; it’s a cultural lightning rod. Since its release, it has sparked uncomfortable yet urgent conversations around adolescence, violence, loneliness, and the murky corners of the internet. At the heart of this storm lies a term thrown casually by the character Jamie Miller (Owen Cooper): incel. But what does that word really mean, and why has it become such a critical concept in today’s discussions around youth and mental health?

From empathy to extremism: the twisted journey of a term

Originally coined in the mid-90s by a 25-year-old queer Canadian woman known only as Alana, the term incel—short for involuntary celibate—was meant to foster understanding. It began as the “Involuntary Celibacy Project,” an online space for people of all genders struggling with intimacy to share their stories and find community. Alana’s intention was neither political nor divisive, but deeply human: to provide a safe space for those navigating emotional and sexual isolation.

However, as Alana later lamented in a rare 2018 interview with the BBC, that space was hijacked. By the early 2000s, Alana had moved on from the project, only to see the word incel co-opted by online communities of heterosexual men who reframed their lack of romantic success as a societal injustice. In these spaces—part of what digital scholars call the manosphere—the narrative shifted from self-reflection to misogyny. Members began using the term as a badge of victimhood, fueled by resentment towards women and disdain for the so-called “Chads”—the archetype of attractive, successful men.

These forums promote skewed beliefs, like the “80/20 rule” cited in Adolescence, where 80% of women are allegedly only interested in the top 20% of men. According to the protagonist Jamie, these ideas offer a grim comfort, creating a scapegoat for his sense of alienation. But far from harmless venting, such ideologies have been linked to real-world violence, from online harassment to mass attacks.

The role of ESI in preventing toxic ideologies

According to sexologist and psychologist Mariana Kersz, it’s precisely this emotional and sexual void that the ESI (Educación Sexual Integral or Comprehensive Sexual Education) aims to address. As Kersz explained in an interview with Clarín, the real tragedy lies in how societal neglect of youth emotional needs leaves a vacuum readily filled by extremist online communities.

“Adolescence exposes what many families don’t want to see: the devastating consequences of not listening,” said Kersz. She emphasizes that the original concept of incel was never about hate. Rather, it reflected a shared experience of loneliness and disconnection. “The lack of sexual or emotional experience shouldn’t be treated with shame or contempt,” she adds.

For Kersz, the true value of ESI is not in teaching anatomy or risk prevention, but in fostering emotional intelligence. It allows young people to challenge gender stereotypes, understand consent, and express desires without fear. In other words, it builds a foundation where empathy trumps resentment.

Crucially, ESI also undermines the heteronormative narrative that reduces sex to a narrow, genital act between a man and a woman. “Sexuality is vast,” says Kersz. “It has phases, emotions, and multiple expressions. We need to make sure children and teens grow up knowing it’s okay to feel, question, and talk.”

Why this matters now more than ever

In the digital age, where an algorithm can push a vulnerable teen from a harmless video to a radical forum in minutes, understanding the true meaning of incel is more than a semantic debate—it’s a public health issue. The term has evolved from a cry for help into a coded threat, and it reflects a wider crisis of emotional literacy among youth.

Parents and educators often focus on academic performance or screen time, but as Adolescence reveals, the deeper issue is emotional abandonment. The rise of incel culture among teens isn’t about sex—it’s about a hunger for connection, understanding, and identity. As Kersz wisely notes, therapy and conversation are tools, not taboos: “No one deserves to live with an emotional weight that becomes unbearable.”

As society reckons with a term that has gone from support group to symbol of hate, the challenge is to reclaim the narrative. If we want to prevent the next Jamie Miller, it starts with asking the hard questions, listening to the quiet pain, and making room for conversations that matter.